Lesson #2: The Iceberg Theory

Hey writers, Savannah here! 👋 I’m a Reedsy blog editor, a judge for our weekly short story contest, and a short fiction writer — which means I spend a lot of time thinking about what goes into a great story.

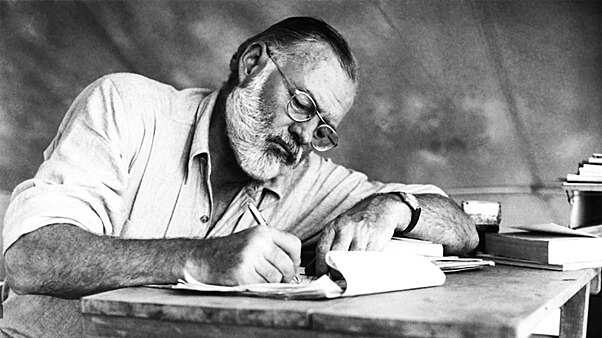

Today, I want to go over one of the most influential storytelling principles behind SDT: Ernest Hemingway’s “Iceberg Theory.”

What is the Iceberg Theory?

This theory, also called the theory of omission, posits that the best writing reveals only a few details at a time, effectively keeping the rest “below the surface” — just like how the bulk of an iceberg lies hidden beneath the surface of the ocean.

Hemingway began formulating the Iceberg Theory as a young journalist writing news briefs. Years later, in reference to one of his early short stories, he would write the following:

I omitted the real ending [...] on my new theory that you could omit anything, and the omitted part would strengthen the story.

This is the Iceberg Theory in a nutshell: giving readers just enough that they can draw their own conclusions about what “lies beneath.” As Arielle touched on yesterday, this is much more satisfying than telling them outright.

How to use the Iceberg Theory with SDT

Of course, minimal information does not make for good writing in and of itself. You still have to ensure that information is evocative and intriguing enough to engage readers. That’s where SDT comes in!

Here’s another example of the Iceberg Theory in action, with a strong description from the opening of Celeste Ng’s Everything I Never Told You:

Lydia is late for breakfast. As always, next to her cereal bowl, her mother has placed a sharpened pencil and Lydia’s physics homework, six problems flagged with small ticks. Driving to work, Lydia’s father nudges the dial toward WXKP, Northern Ohio’s Best News Source, vexed by the crackles of static. On the stairs, Lydia’s brother yawns, still twined in the tail end of a dream. And in her chair in the corner of the kitchen, Lydia’s sister hunches moon-eyed over her cornflakes, sucking them to pieces one by one.

There are a few subtle showing mechanisms at work here: crackles of static from the radio, the taste of cornflakes. But far more compelling is what the scene implies about the Lee family as a whole — all beginning the morning separately, all described in relation to middle daughter Lydia (who, as readers know, will not be coming to breakfast).

Ng never explicitly states that “Lydia kept the family together; without her, they would fall apart.” Yet as the novel progresses, it becomes clear that this is the iceberg lurking beneath that very first passage and many passages to follow.

Tips for applying the Iceberg Theory yourself

On that note, here are a few tips on how to use the Iceberg Theory when SDT’ing:

1. Use it to hint at complex dynamics and histories. The Iceberg Theory works well in the context of relationship dynamics, especially those with a long history. The larger the underwater iceberg, the more weight your descriptions will hold — and the more satisfied readers will be as chunks are revealed.

2. You can tell a little bit if it serves the showing. Sometimes to dig deep with your showing, you first need to establish context. Ng does it with that first line where she tells us, “Lydia is late for breakfast.” Don’t be afraid to tell if it balances or enhances your showing!

3. Don’t omit what you don’t know yourself. The Iceberg Theory is not an excuse for incomplete character or story development; if you're implying something rather than confirming it, it should be for an intended effect, not mere laziness. As Hemingway puts it: “A writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing.”

Writing exercises

The Iceberg Theory is tough to apply in isolation — you need a fully fleshed-out character or story, a proper iceberg, in order to deliberately show a fraction of it.

Need help developing the building blocks of your novel? Sign up for our three-month writing master class, How to Write a Novel, and get instant access to lessons on character development, setting, plot, and more.

That said, if you don’t have your own story or characters mapped out yet, you can try these exercises with existing characters (from a book, film, TV show, etc.) that you know incredibly well!

- Write a scene in which a character’s behavior or reaction to something is affected by a past experience — without saying what that experience was.

- Write a monologue on a seemingly arbitrary subject that deeply reflects that character’s worldview.

- Write a description of someone or something whose appearance, unbeknownst to the reader, used to be completely different.

When in doubt, remember that less is more, and ice is nice ❄️

Have fun with those exercises, and stay tuned for tomorrow’s lesson on establishing atmosphere and setting with our resident worldbuilding expert, Jenn.

— Savannah

Recommended Resources

Brought to you by Reedsy

Reedsy is a publishing network that connects writers with the world's best editorial and book design talent. As part of our mission to help authors bring their stories to life, we offer over 50 free writing courses and a premium three-month course on How to Write a Novel.

|

|||

|

Top publishing professionals can help make your writing dreams a reality. Sign up to meet them. |

|

Copyright © 2026 Reedsy, All rights reserved.